A defaced stencil of a military officer on a Yangon street, a quiet act of protest against Myanmar’s coup. ©THROAT, February 2021

Myanmar’s Artists: Creativity Amid War and Exile

Author: Darko

Inside Myanmar, the art scene is trying to survive, edging away from overtly political work and other perilous terrain. The artists who can still make things happen continue to push forward. Aye Ko, a contemporary artist and the founder of New Zero Artspace, is hosting artist residencies in Hmawbi Township, northwest of Yangon. Htein Lin has opened a new gallery in Kalaw, a hilly town in Shan State. Everyone understands that most funding will eventually disappear and that they will be left to start again, largely on their own. A kind of self-reliance has taken hold.

The artists now living in exile are struggling to keep their message alive, simply to survive wherever they've landed. Many are confronting an identity crisis shaped by unfamiliar circumstances, piecing together new lives while carrying the burden of being a voice for the voiceless. Inspiration is hard to come by amid the grind of day-to-day survival.

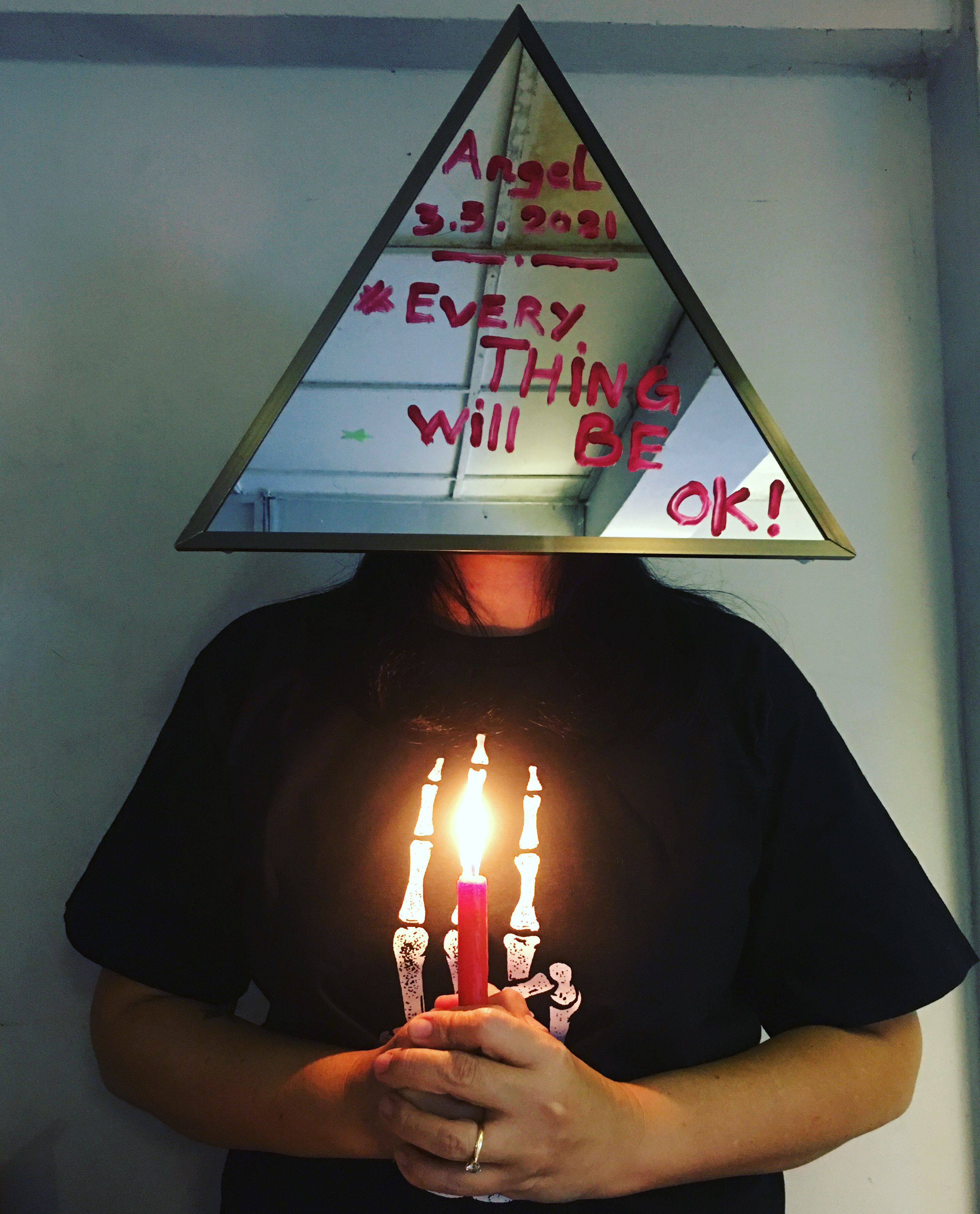

"I'm not very creative here. I've lost my inspiration. I'm working nine hours a day, six days a week, just trying to keep my family afloat. I can buy all the materials I need, but I can't manage the emotional collapse that comes whenever I try to make art. I completed my yearlong project, Response365, during a brutal period—beginning on February 1, 2021—with the drive to respond to the illegal military coup. After arriving in the U.S., I received very few invitations to participate. In Myanmar, I was more involved and active in the art scene. But here, with the language barrier and without a network, I can't break into Austin's art scene yet. I'm unknown, and I feel pretty disconnected," Emily Phyo, a contemporary feminist artist who fled the country and resettled in Austin, Texas, told me.

In Myanmar, some audiences have begun to boycott artists who continue their creative work while the country is at war. The backlash has left many artists feeling intimidated about showing their work, and, in some cases, demoralized about creating at all.

Chaw Ei Thein, an exiled artist living in New Mexico who fled Myanmar in the nineteen-nineties, told me, "If the artwork or the artist doesn't support the junta, it should be fine." She described her frustration that some well-known artists in the U.S. still feel unable to post freely on Facebook: if the military's watchers discover their political art—and can trace their families' whereabouts in Myanmar—those relatives could face serious repercussions. Many families have pleaded with them to delete politically sensitive posts altogether.

In the art market, there are signs of renewed interest from China and Southeast Asia, particularly Singapore. Some works of classic realism and modern painting have been sold within exclusive circles, pieces known in Burmese as kyeik wine, long rumored to be linked to money laundering. Art lovers worry that these valuable paintings are being snapped up by cronies seeking to burnish their public image, rather than by serious collectors, galleries, or museums. Among the prominent buyers is the Yangon Gallery, owned by a son of the junta's chief, Min Aung Hlaing. Beyond such élite circles, however, artists in Myanmar are barely surviving amid the country's widening civil war. Other creative industries—film, music, literature—are now published and distributed almost exclusively by those with ties to the junta.

Ko Thura, known as "Zarganar," which means "tweezer," is a famous comedian and a filmmaker. He is well known for his political satire and comedy. He was arrested multiple times and banned from film and public appearances from time to time, way before the democratic transition. Even though he did not speak out much after the coup, he was detained again. Now he is released, but is going through a financial challenge. He is struggling with being a ghostwriter and teaching screenwriting.

On top of that, censorship, once a fixture of daily life, has returned. Artists are again required to submit their paintings and other works for approval before any exhibition. Many are already contending with their own self-censorship: if the board deems a piece political or otherwise sensitive, the artist can be imprisoned with no clear sense of when, or whether, they will be released. Even audiences take risks; in some cases, merely clicking "Like" on a political artwork on Facebook can draw unwanted attention.

Getting artwork out of the country has become a nightmare. A certificate of permission is now required even to clear airport security. "D.H.L. asked for it, too, when a friend of mine tried to ship some paintings a couple of years ago," Chaw Ei Thein told me.

Many well-known artists no longer dare to travel abroad, fearing that they might be profiled and detained at the airport. Others cannot travel at all: their passports have expired or have been revoked. Still others live under quiet surveillance, monitored by informers in plain clothes.

Organizers, too, are under pressure from both the public and the authorities. They want neither to provoke trouble nor to be publicly shamed. Cultural institutions such as the Institut Français de Birmanie and the Goethe-Institut continue to provide grants, but they face mounting challenges of their own. In one recent instance, a documentary film was barred from being screened.

For more than a decade before the coup, outsiders—international donors, nonprofits, investors—arrived hoping to witness something distinctive in Myanmar's art scene: activism, feminism, a galvanizing edge. They often seemed to come with a script in hand, searching for artists who could play the roles they had already imagined, rather than offering the unencumbered support needed by those pursuing the work they loved. And now? Who is helping them now? Aside from a handful of opportunists from China and Singapore, almost no one. Is there a way to help? There are many, if one is willing to look.

Five Ways to Help Myanmar’s Artists

Communicate: Reach out directly. Many artists remain accessible online, even if they are working quietly or from exile.

Support Technically: Offer mentorship, skills training, or guidance in navigating digital platforms and creative tools.

Fund Them: Even modest grants can make an outsize difference.

Pay Attention: Share their work. Visibility is a form of protection—and, often, power.

Create Exchange: Bring them into global conversations. Include them in residencies, fellowships, and collaborative projects.

Myanmar's artists still deserve to be seen, heard, and talked about. Visibility is power.

Emily Phyo is a Burmese visual and performance artist born in Yangon. Prior to the 2021 military coup in Myanmar, she operated a small tailor's shop in a Yangon market while actively engaging in the local art scene. Following the coup, for her safety, she relocated to Austin, Texas, in 2022, where she continues her artistic practice. Phyo's work often explores themes of feminism, political critique, and social fabric.

Artworks by Emily Phyo

Tools of Defiance, Emily Phyo, 1170x1139 px, 2021

Digital Image

No More Silence, Emily Phyo, 2500x2500 px, 2021

Digital Print

Barbed Freedoms, Emily Phyo, 3024x3024 px, 2021

Digital Image

Silent Salute, Emily Phyo, 3024x3024 px, 2024

Digital Print

Reflections of Hope, Emily Phyo, 2880x3568 px, 2021

Digital Print