STORIES

Myanmar’s Artists: Creativity Amid War and Exile

In a country unraveling under military rule, the artists who once dared to speak now whisper—or fall silent. Some paint in exile, struggling to summon inspiration while navigating survival jobs and cultural dislocation. Others, still in Myanmar, work behind closed doors, knowing that a single brushstroke deemed political can lead to prison. “I can afford the materials,” Emily Phyo, a feminist artist now living in Texas, told me. “But I can’t afford to feel.”

The Weaponization of Image: A Myanmar Artist's Strategic Resistance

There are thousands like him; graphic designers, photographers, graffiti artists, poets, painters. They are producing underground work, smuggling symbols, building visual languages of resistance. They are documenting the authoritarian decay as it happens.

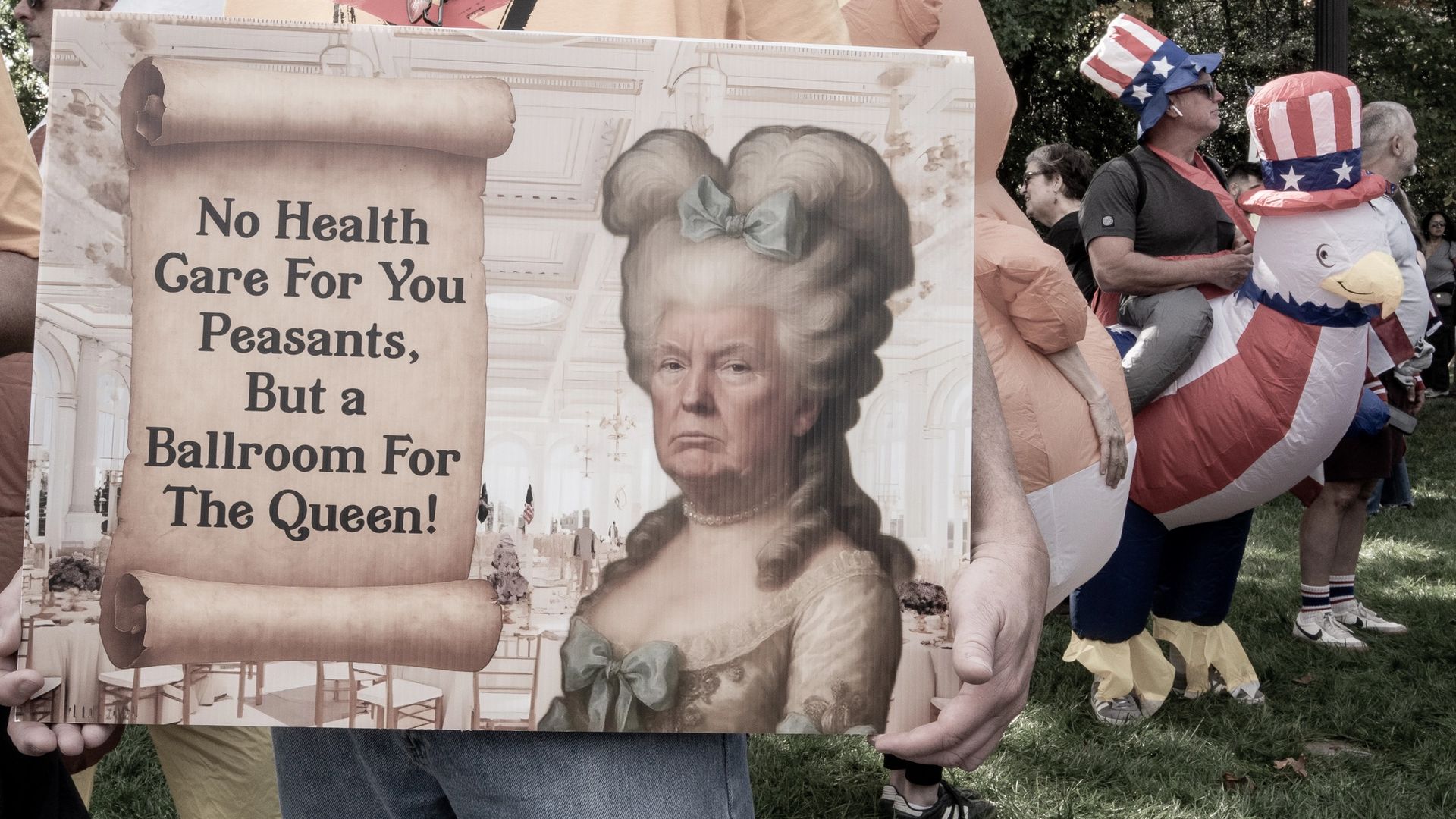

Dominion or Delusion: Why Our Survival Depends on Evidence, Not Vibes

Arielle made a choice that shouldn’t feel radical. Her father’s health had buckled, and the quiet Florida retirement they’d planned could no longer keep pace with the bills. In Portugal, a doctor saw him the week they arrived—efficient, affordable, almost disarmingly humane. It wasn’t an act of defiance, or something “un-American.” It was simply what survival looked like.

Morgana Wingard Unfiltered: Capturing Raw Truth in a Chaotic World

In this feature, we sit down with Morgana Wingard, a photographer, filmmaker, and storyteller whose lens captures the pulse of humanity in crisis. Her path began in a middle-school darkroom and led her to document the Ebola outbreak in Liberia and, later, the COVID-19 pandemic across the United States. Her latest project, Airborne Firefighters, turns her gaze to the crews battling wildfires from the sky.

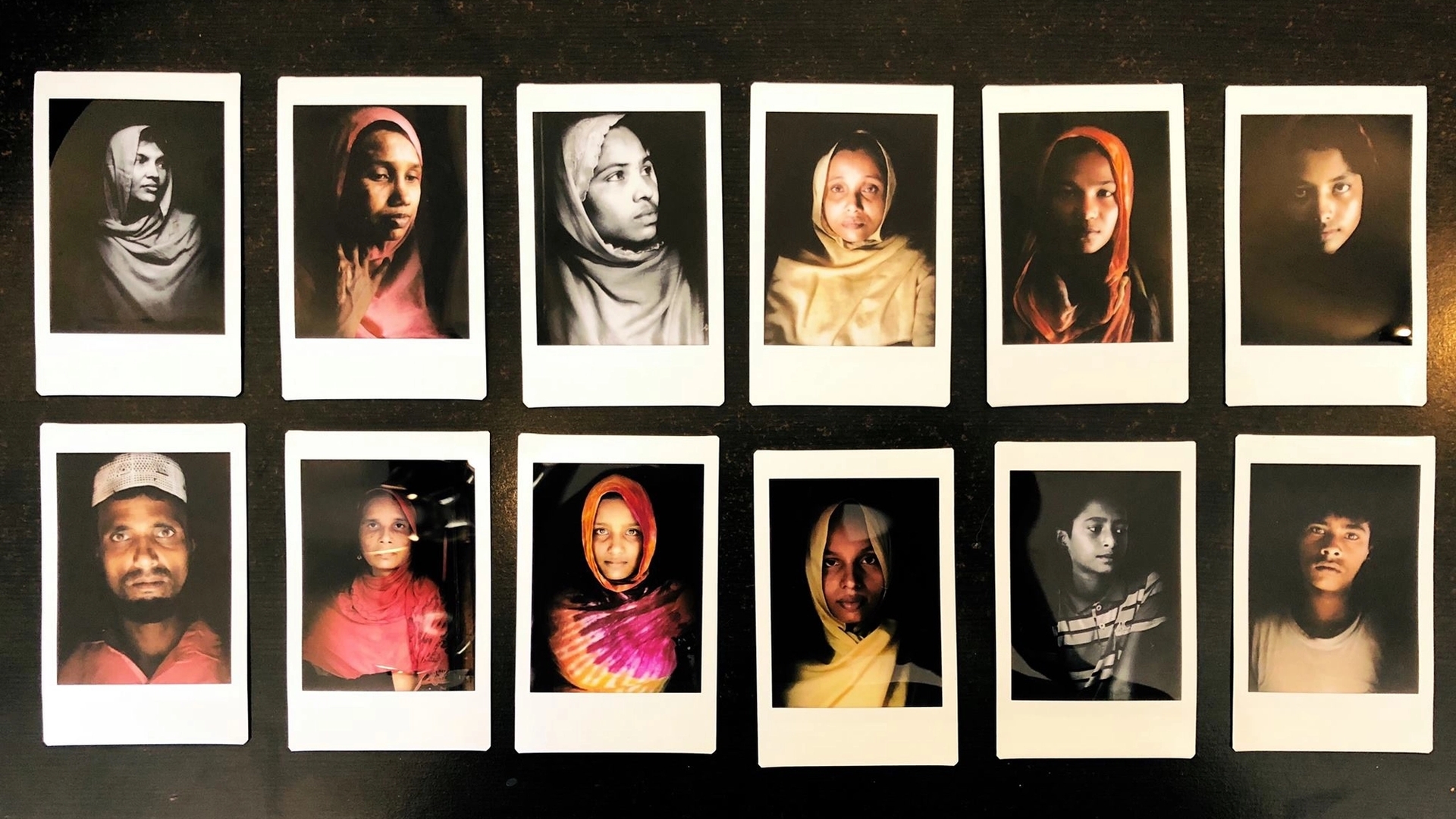

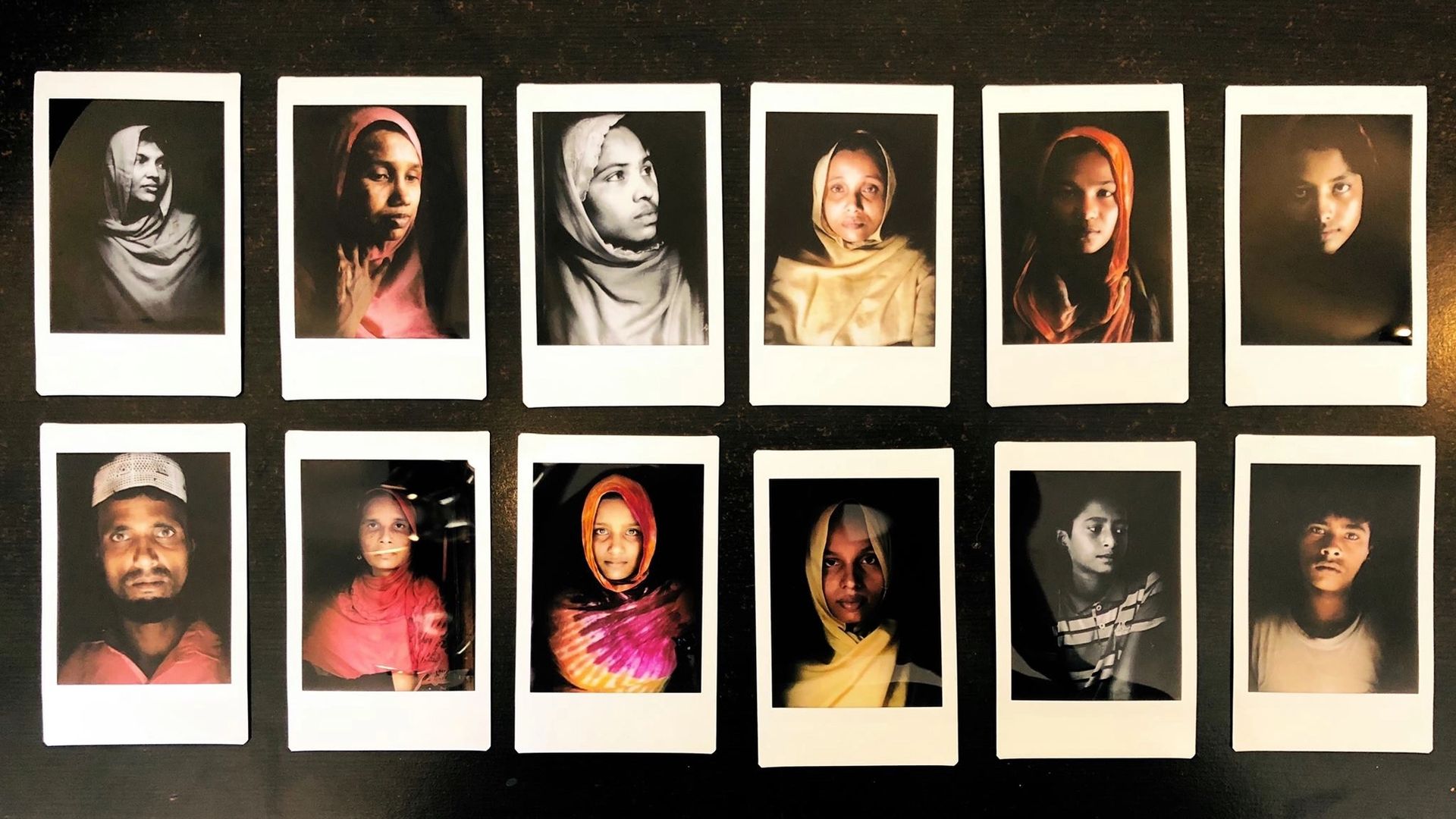

Against Refugee-ness

The crisis I observed was not the crisis being represented. Refugee-ness is a visual grammar: unwritten rules insisting refugees look a certain way to be recognized. It edits people into narrow roles: the helpless victim or the criminal threat. It disciplines what the public is permitted to feel.