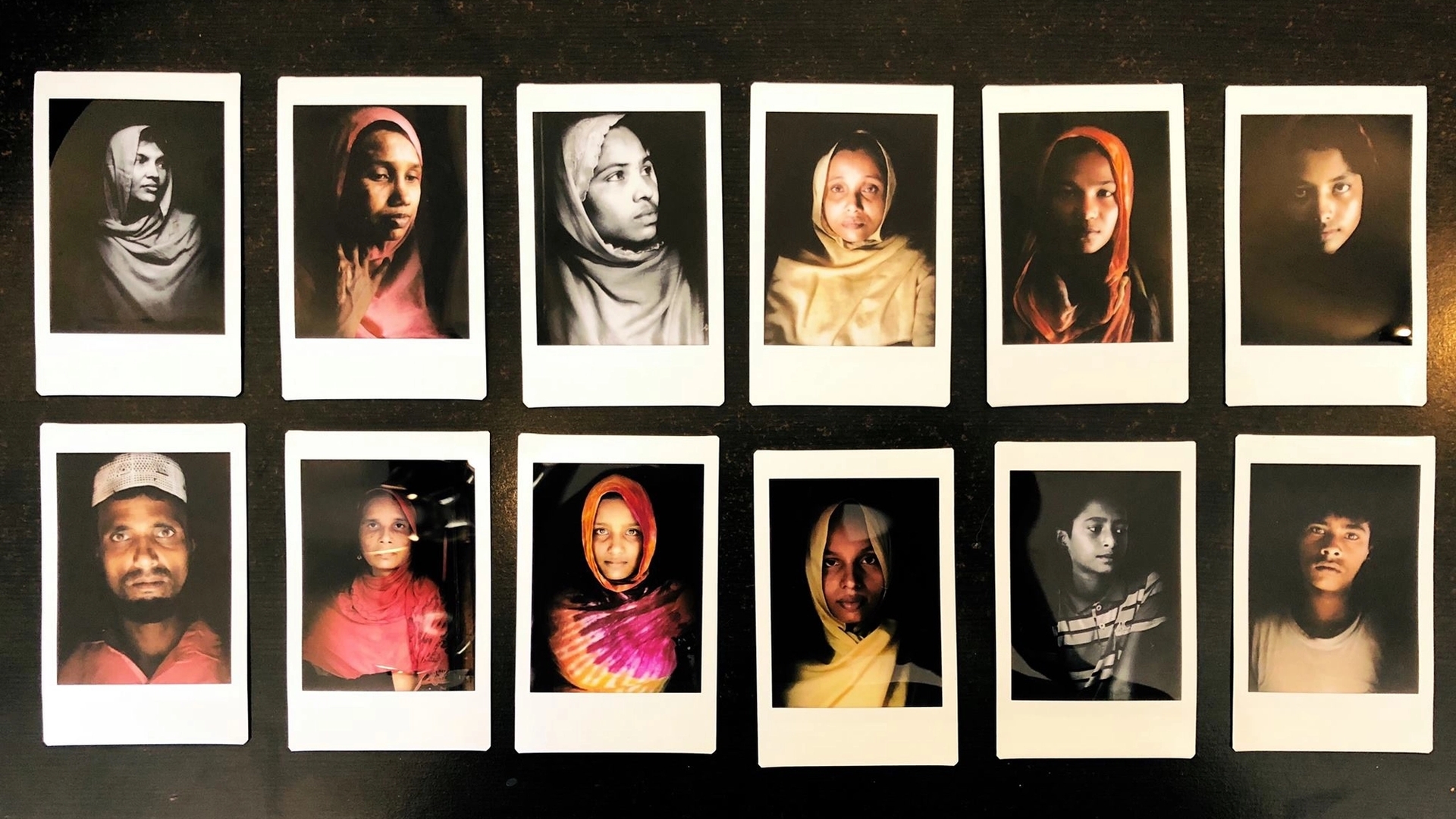

Twelve portraits, twelve individuals - refusing the familiar “crowd” image that erases names, faces, and lives.

Against Refugee-ness

Author: Shafiur Rahman

Let’s assume you are a humanitarian worker. Or a photographer or journalist. And your assignment is a project in the Rohingya refugee camps of Bangladesh where almost 1.1 million refugees live. Let’s say you are media savvy. You have done your homework. You will arrive with a set of images in your head.

Most likely, that will be the public record - the photographs that had travelled across screens and front pages in August 2017. Columns of people crossing muddy borderlands; mothers clutching babies; children with wide, exhausted eyes; bodies collapsing on the shore after a boat journey; endless queues under rain or hard sun. The message in those pictures was blunt and immediate: these were helpless people fleeing a ruthless genocidal campaign by the Burmese military, and they needed urgent humanitarian rescue.

The imagery you will actually encounter on the ground will be vastly different: a society being rapidly constructed under extreme pressure; families negotiating space and privacy; boys turning scraps into toys; women building routines inside chaos; people arguing, laughing, bargaining, praying, repairing. I didn’t mean the suffering wasn’t real. It was. But the camps were not only suffering. They were also life, in all its stubborn detail.

I started working in the Rohingya camps in December of 2016. That gap, the distance between the photographic story and the lived reality, began to trouble me. The crisis I was observing was not the crisis I was seeing represented.

Over time I realised the problem wasn’t only what was being photographed, but how the Rohingya were allowed to appear.

There was a peculiar “refugee-ness” to the pictures; a set of unwritten rules that insisted a refugee must look a certain way in order to be recognised as a refugee at all. Refugee-ness is a visual grammar. It edits people down to a narrow role - the desperate victim, the passive recipient, the eternal sufferer. Or when the political mood shifts, the criminal, the burden, the contaminant, the security risk. It is photography that doesn’t only depict displacement; it quietly disciplines what the public is permitted to feel about displaced people.

This matters because journalism does not sit outside humanitarian crises. It is part of the machinery. Media helps deliver the “preferred reading” of a crisis - who deserves sympathy, who deserves suspicion. So that we may decide who is beyond obligation. In any country, public opinion is not formed only through speeches and policy briefs; it is formed through images repeated until they feel like common sense.

In August 2017, Myanmar’s military launched a brutal campaign against the Rohingya population of western Myanmar. In the space of weeks, close to 800,000 people crossed into Bangladesh. At the start, the dominant imagery cast the Rohingya as unfortunate people persecuted for their identity - people arriving in rags, hungry, dirty, half-starved, carrying children, carrying elders, carrying nothing but what could be held in two hands. The pictures asked the world to feel pity, shock, and moral urgency.

Alongside this, another visual story was built - Bangladesh as saviour. The government’s political messaging gathered quickly around the idea of benevolent national rescue - banners and billboards celebrating the opening of borders; photographs and staged moments of comfort; the leader embraced as protector and annointed “Mother of Humanity.” The crisis was framed not only as Rohingya suffering, but as Bangladesh’s generosity.

Then the “action” moved from the border to the camps. The camera found the queue. Masses waiting for aid; bodies in the mud; hands outstretched; tarpaulin and bamboo; the crowd shot from above until individuals dissolved into a single amorphous shape. The imagery established total dependence. It also trained audiences, donors, officials, and citizens, to see the Rohingya primarily as a problem to be administered.

Within months, the narrative turned. The pity images thinned out. In their place came a new repertoire. This was the refugee as long-term economic burden; the refugee as demographic threat; the refugee as disease vector; the refugee as environmental destroyer; the refugee as criminal. On social platforms and regional online outlets, dehumanising claims multiplied, about rapid breeding, about social decay and danger arriving from the camps. The crisis that had begun as a humanitarian catastrophe was rebranded as a national risk.

And once that turn was made, policy followed it with grim ease. The list is long - internet bans; SIM confiscations; fencing and barbed wire; harsher restrictions on movement; threats of repatriation; the relocation of people to a remote island; the steady tightening of a life already governed by decree. The camps became not only places of shelter, but landscapes of confinement and the visuals began to match the politics.

In recent years the most common images in Bangladeshi coverage have not been mothers at the border or crowds at food distribution. They are arrest photographs. Rohingya men displayed as suspects; bodies positioned between armed officers; faces half-hidden; the “sandwich” image designed to produce one feeling above all others: threat. The alleged crimes vary - from yaba trafficking to arms smuggling to factional fighting. But the photographic treatment stays consistent, even for acts that are not crimes in any moral sense, for example attempting to leave Bhasan Char; marking 25 August as Genocide Day; selling a T-shirt that expresses identity. The sub-text rarely changes. Rohingya equal criminal; Rohingya equal disorder; Rohingya equal a problem for law-and-order to contain.

This is how refugee-ness works at the punitive end of the spectrum. When pity is no longer politically useful, the refugee becomes the figure who legitimises restriction. And when those images become the dominant public record, they do more than report events, they narrow the range of public emotions until empathy looks naïve and solidarity looks dangerous.

Susan Sontag warned that photographs do not simply deliver reality; they shape it. Images can make suffering “immediate” and “felt” but they can also turn people into objects, tokens, and categories. They can arouse compassion that quickly becomes inert if it is not translated into action. “Compassion is an unstable emotion,” she wrote. “It needs to be translated into action, or it withers.” And she insisted we think about what images invite us to do - whether they challenge power or quietly reconcile us to the inevitability of other people’s misery.

What I have watched in Bangladesh is not only compassion withering, but compassion being replaced, that is, pity drained out and refilled with suspicion. A population once shown as persecuted has been remade, visually, into a population that deserves containment. Over-saturation of "pity images" is exactly what paved the way for the "threat images.”

This is why it matters who holds the camera.

Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh are not given formal refugee status. Rights do not arrive as rights; they arrive as permissions and permissions can be withdrawn. Daily life is shaped by camp authorities and security agencies; movement is restricted; formal work is prohibited; education is capped; phones are confiscated; connectivity has been cut. Even the landscape - barbed wire, checkpoints, watchtowers - signals a political message before anyone speaks.

That landscape has symbolic consequences. Barbed wire does not only block a path; it tells the public what kind of people are inside. When journalism repeatedly shows a fenced population mainly through the lens of criminality, the humanitarian catastrophe starts to disappear from view.

The political question - what happened to these people, and what is owed to them - gets replaced by a managerial question. How do we control them?

Rohingya photographers disrupt this. Not because they create “positive” propaganda, but because their gaze carries a different kind of truth: the truth of proximity, of continuity, of the everyday. They photograph not only what shocks, but what persists. They show texture like workarounds, relationships, humour, fatigue, pride, grief, ingenuity. They show the camps as lived space rather than a stage set for pity or fear.

In that sense, the Rohingya photographer is both narrator and witness. Their work translates complex humanitarian and political realities into something immediate and human without transforming people into symbols. That is exactly the intersection THROAT is asking for - art that speaks up, testimony that refuses to be decorative.

There are hurdles, of course. Many Rohingya photographers have little formal training, limited language access, limited platforms, and genuine fear. The equipment can be seized; mobility is restricted; being visible carries risk. And yet the need is urgent precisely because the dominant institutions - media, humanitarian branding, state narratives - have repeatedly failed to represent the Rohingya in a way that is full, transparent, and ethically awake.

The simplest argument for Rohingya photography is agency: people should represent their own lives. But the harder argument is accuracy. To understand what a long-term refugee regime destroys, forces, or produces, the insider’s record is not a courtesy, it is essential evidence. Without it, our information is not only incomplete; it is wrong.

When Rohingya photographers are exhibited, credited, and paid, the public record changes. The Rohingya re-enter the frame not as a mass, not as a threat, not as a helpless prop in someone else’s moral drama, but as people with voices, choices, contradictions, and futures that have been stolen and yet are still imagined.

And that, finally, is what I want to refuse when I refuse refugee-ness: the idea that the Rohingya can only appear in the world as suffering or as danger. They have been forced into exile. But they are not required to be visually exiled from their own story.

Shafiur Rahman is a journalist and award-winning documentary filmmaker who has reported on the Rohingya crisis from Bangladesh and Myanmar since 2016. He publishes Rohingya Refugee News, a newsletter on displacement, humanitarian governance, and the politics of representation, and he founded the Rohingya Photography Competition to platform Rohingya photographers. His work examines how images, policy, and everyday camp life shape what the world is willing to see.

Artworks by Shafiur Rahman

One Last Look, Shafiur Rahman, 2528x1422 px, 2017

Digital Image